The whole sentence, from The Message, provides a fuller context:

Tornadoes and hurricanes are the wake of His passage,

Storm clouds are the dust He shakes off His feet.

What if they really are—clouds, the dust of God's feet? Just as we can track little Pig-Pen through the frames of a Charles Schulz Peanuts panel by the trail of detritus he leaves in his wake, what if we can track God's path through the heavens by the clouds that are the dust from His feet?

Give me credit for knowing that clouds have a scientific explanation, and for knowing that anthropomorphisms were common to the ancients when describing their deities (including the Bible's authors).

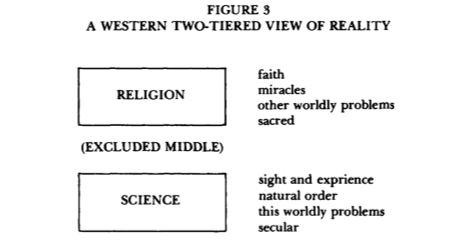

But I also believe in what missiologist Paul G. Heibert called "The Flaw of the Excluded Middle" in his seminal article by the same name that lit up Christendom's "chat rooms" in 1982. Heibert, a missionary-scholar, had found his Western, scientific worldview totally inadequate to explain the spiritual phenomena he encountered in non-Western, non-scientific cultures. There, he found an interaction between heaven and earth that the West, on the basis of observable science, didn't believe existed: the overlap of heaven and earth, spirit and matter—a third dimension where the spiritual activity of heaven impacts the physical activity on earth. As a gentle rebuke to Western Christianity, Heibert accused us of having a flawed cosmology—flawed for having excluded (ignored) the middle realm that exists between heaven and earth.

As a biblicist, he knew that middle realm existed in Scripture (e.g., Daniel 10:1-21; 2 Corinthians 11:12-15; 12:1-6), but it had been excluded by Enlightenment-bred thinkers. He preposed that the middle domain be re-acknowledged as a way of better explaining what we observe on, and from the vantage point of, earth.

Back to clouds—I have no way of knowing whether they are the dust of God's feet or not; whether they tell us anything about the activity of God in heaven. But the more I find myself thinking like a scientist ("No, clouds having nothing to do with God"), the more willing I am to simply say, "I don't know." Why be dogmatic about something I can't possibly know for sure? Why treat the ancients, who wrote such things, as primitive poets rather than insightful realists?

My goal in life is to see God's footprints and fingerprints everywhere they exist and to know His movements better as a result. Not to see what isn't there, but not to miss what is.

No comments:

Post a Comment