Because I work at home and travel very little, I have no need at present for a digital book reader. Even if I needed one, I would regret having to use it, though I recognize their utility. There's still something I resist about the sudden transformation of books from works of craft and art and utility to utility alone. To wit . . .

Because I was captivated by the Swedish movie versions of Stieg Larsson's Millennium Series of novels (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest), I decided I wanted to read the books themselves to see the author's original version of the stories. (Ten volumes were planned, with only three finished and published before Larsson died suddenly.)

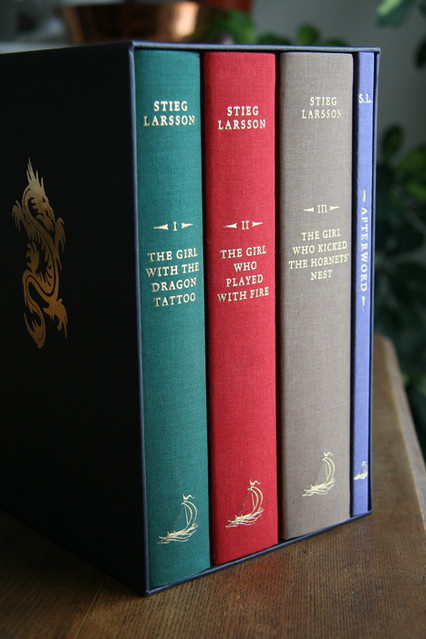

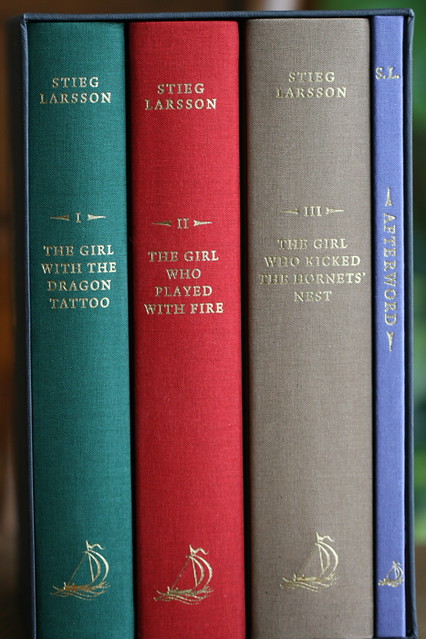

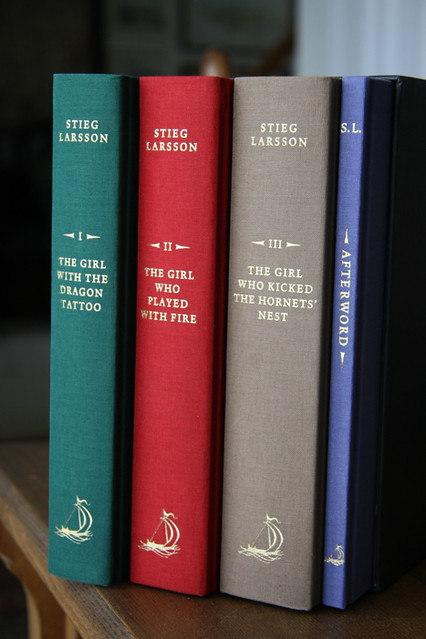

The American publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., issued a nice four-volume boxed set just before Christmas—the three novels plus a fourth Afterword volume containing correspondence from the author as he wrote the stories and had them published. I wasn't enamored of the Knopf edition, but was attracted to the British edition—unfortunately now out of print. But I found a bookseller in San Francisco who had a still-shrink-wrapped boxed set from the British publisher, MacLehose Press, an imprint of Quercus. The British edition was typically understated compared to the American Knopf edition. So I bought them.

It's not hard to see why many people prefer to own finely printed and bound volumes compared to digital editions. The pictures below remind me of the Seinfeld episode where Jerry asks George why he bothered keeping copies of books once he's read them. This is part of the reason why:

This gold dragon—highlighting the "Dragon Tattoo" motif—is imprinted on the side of the slipcase:

Even the thread used to sew the signatures together is beautiful! But—evidence that these are still mass-produced volumes: insufficient sanding of the edges (left) and a bubble of glue (right). But the picture shows the signatures of which books are made—the individual mini-books that are printed, then bound together to create the volume—nineteen signatures in this volume:

Fifteen in this one:

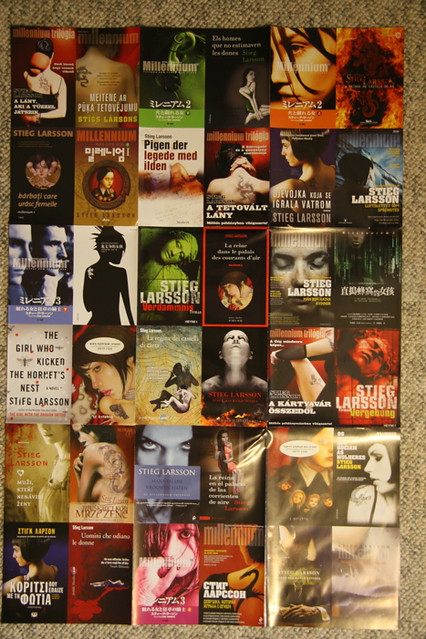

The British edition (unlike the Knopf edition) also came with a wall poster containing images of 36 different covers of the novels created by foreign publishers. More than 65 million copies of the novels have been published in hard copy, and well over a million copies for the Kindle have been purchased:

Not only are books beautiful themselves, repositories of books are as well. For Christmas, my son David gave me a gorgeous volume titled The Most Beautiful Libraries in the World (Abrams, 2003). It contains breathtaking large-format photos of some of the most beautiful and thoughtful "buildings" constructed throughout history to store the collected knowledge and art of man.

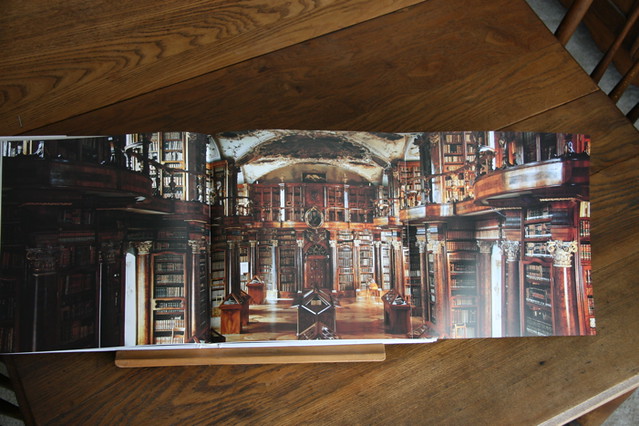

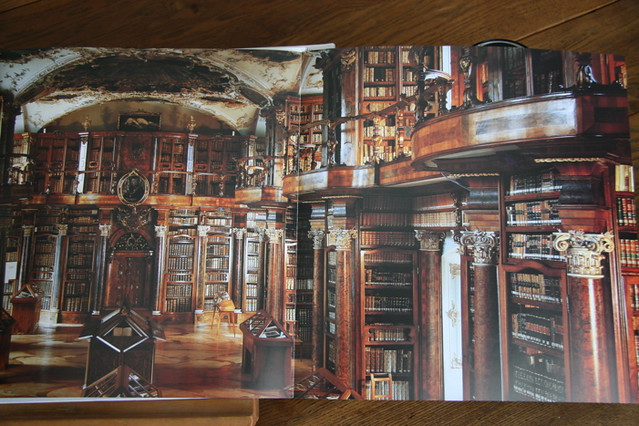

This is a foldout spread of the Great Hall in The Abbey Library of Saint Gall in Switzerland:

And a closer look at two of the panels:

I sent David the following reflections after my first perusal of this book:

1. In the non-American libraries, where collections are much older, imagine the labor that went into the binding BY HAND of these millions of volumes. Even though the printing press came online around 1455, books were still bound by hand, right? And not just the binding, but the gilding and lettering on the spines, etc. The man-hours represented by the binding of millions of volumes is staggering -- all for the preservation of knowledge.

2. Again, in the non-American libraries, I was struck by the admixture of art and literature. Libraries could have been sterile warehouses with shelves -- just a place to catalog and store books. But they were stored in the equivalent of palaces and cathedrals. The libraries themselves represent the height of art, sculpture, and architecture of their day. It speaks well for how books (and manuscripts and music scores and important papers) were viewed -- on a plane with royalty and deity, so ornate and thoughtful were their places of storage.

3. The contrast between American and European libraries. I think only two American libraries are featured -- the Library of Congress and the Boston Athanaeum. Purely from the perspective of the photos of the books on the shelves, the American library books are smaller, newer, less ornate than the books in the European libraries. That's obvious and easy to explain, of course -- America is a younger nation, etc. But it must also say something about the intellectual history of the two cultures -- our libraries look "lighter" than the European libraries. More than once, in looking at some of the European libraries, I thought, "That's what the library at the Biltmore House (Asheville) looks like." . . . It's because George Vanderbilt basically imported books from Europe (as he did furniture, tapestries, art, etc for the house) that it looks so much like a European library.

Solomon had it right: "Of making many books there is no end" (Ecc. 12:12). And it's a shame that they (save one) will wilt before the renovating flames yet to come. The destruction of the great Library at Alexandria in 48 B.C. (thanks, Julius Caesar), where much of the accumulated knowledge or the world was stored, is a warning to all who would hold books too tightly.

But while we have them, they are a pleasure to have and hold.