Another way to absorb the complete spectrum (theoretically) of major and trace minerals found in ocean water is to eat plants grown in the ocean: kelp, kombu, dulse, arame, laver, wakame, and others, along with dried algae. "Sea salt" theoretically accomplishes the same purpose, but these are "hard rock" minerals, not having gone through the transforming process of being absorbed by a plant and therefore made more absorbable by the body. Asian cultures have eaten sea vegetables "forever," but not so much in our American (European-derived) culture.

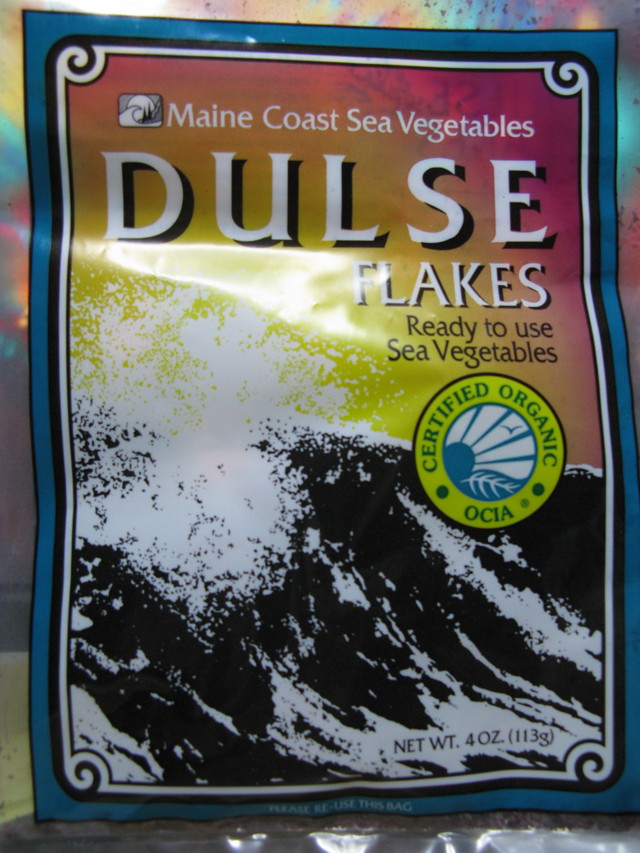

I'm starting by using dulse flakes:

This package contains finely-chopped dulse flakes which I put into an empty Frontier spice bottle (one with extra large shaker holes) to be able to shake onto salads and pasta. I also added a couple tablespoons to hummus I made last night, and it can also be added liberally to soups and stews. The flakes quickly absorb ambient moisture and become soft and "disappear" into whatever they're added to. Because sea water is naturally "salty," sea veggie flakes can serve as a mineral-rich salt substitute.

Of course, anything coming out of the ocean these days is suspect in terms of cleanliness, but better companies supposedly harvest their veggies from relatively clean parts of the ocean. The dulse flakes above are certified organic, which means that the product has passed a measure of analysis in terms of where it was harvested.